When Walton W. Rogers, CLU, ChFC, first qualified for MDRT in 1975, he wore a tie to work every day. And he wasn’t the only one; wearing suits and ties was the standard in that time. But fast-forward 46 years and the expectations have shifted.

Nowadays, Rogers sometimes leaves his tie at home in favor of a more casual look. It’s not simply a sartorial decision; he says it’s the influence of his younger Generation X and millennial coworkers, who eschew a more formal dress code.

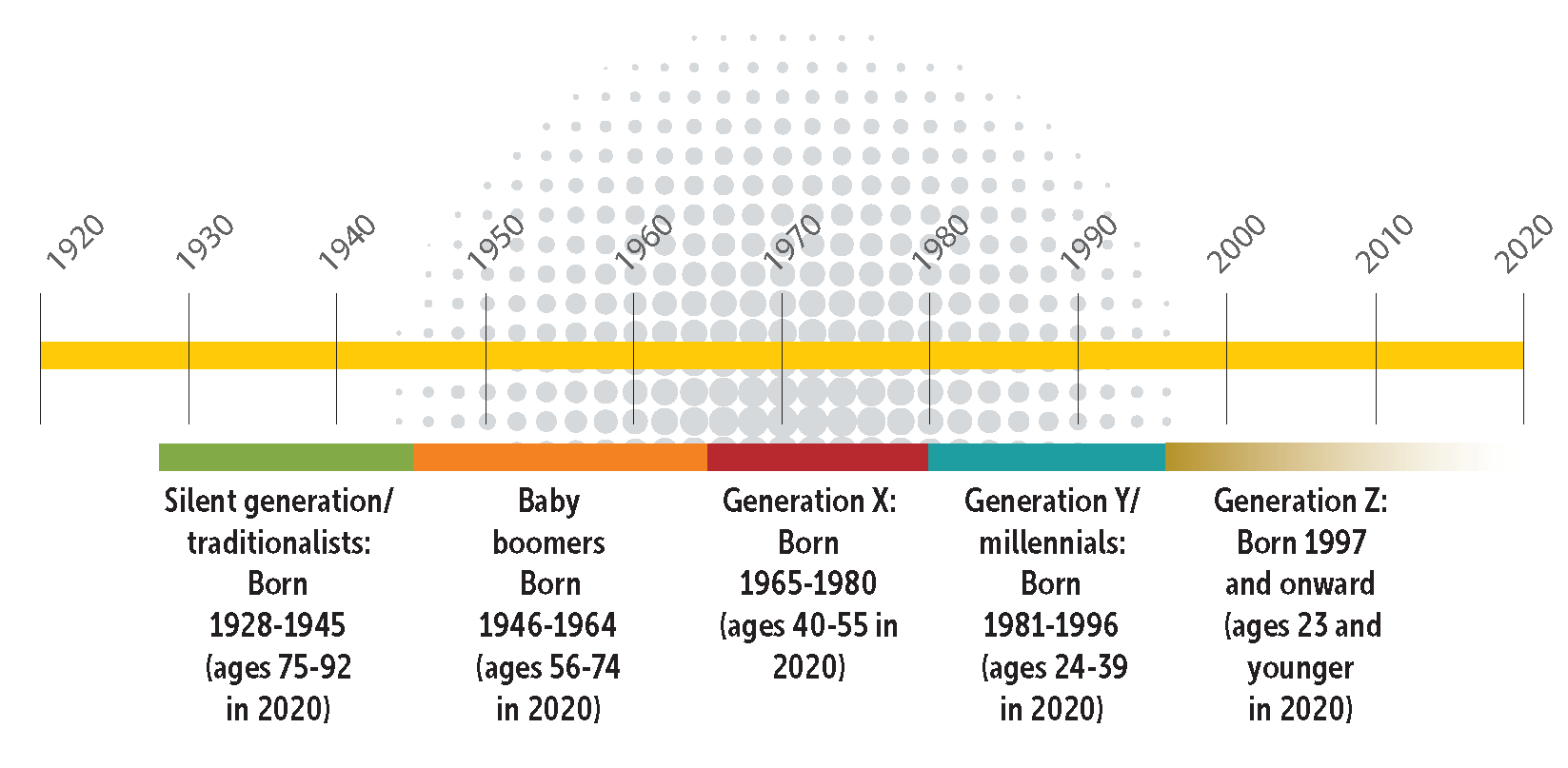

This relatively insignificant change points to a much larger trend across the business world. In 2020, there can be as many as five different generations in the workplace at one time. Millennials, the world’s most populous generation, are becoming more influential. Research predicts that by 2025, they will make up as much as 75% of the global workforce.

Their older counterparts, from baby boomers to traditionalists, are staying in the workforce longer; together, they account for about 27% of the American workforce and 6% globally. Members of Gen X are in their 40s and 50s, settling into leadership positions and currently accounting for more than one-third of the global workforce. And recent college graduates are just entering the workforce; Gen Z is expected to have a dramatic impact on the workplace in the next five to 10 years.

This unique convergence of five generations will impact many offices, opening the door for generational tension — and great opportunity.

A whole new world

There are several reasons for this monumental shift into a multigenerational workplace, according to Tony Lee, vice president at the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). The most significant is that people simply aren’t retiring as early. Longer life expectancy and higher standards of living mean that people are able to work into their 70s and sometimes even 80s because they are healthy and enjoy the work.

The global financial crisis of 2008 also impacted retirement income, so many would-be retirees must keep working to survive.

According to data from Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics in February 2019, more than 20% of Americans age 65 or older were working or looking for work.

As for Rogers, who is 76, he continues working for one simple reason: He likes it.

“Why stop something that’s fun and I’m good at and I get rewarded for doing it?” said Rogers, a 46-year member and 2008 MDRT President from Jacksonville, Florida. “I’ve read about people in my position who are 92 who go into the office. I get it.”

Nonetheless, he says he is slowing down and plans to not be working at the same pace in his 80s.

Lee says that Rogers is a representative example of his generation and gives a good idea of what’s to come.

“Is 80 the new 60? Maybe,” he said. “I would say that what you’re seeing now is the new normal.”

Increasingly, countries with retirement age requirements are raising them. In fact, research from ManpowerGroup revealed that many millennials already expect to work past age 65. In Japan, 37% of millennials believe they will work until they die. That figure decreases to 14% in India, 12% in the U.S. and just 3% in Spain.

The problem with assumptions

As we enter this uncharted territory of truly multigenerational workplaces, challenges will be natural. Older generations often fear the younger ones will come into the office and try to change everything, while younger people assume their elders will be stubborn or unwilling to change anything.

The key, Lee says, is not believing the stereotypes.

“Don’t make assumptions based on the person’s generation,” he said. “Ageism goes across the entire spectrum.”

Ter Chiew Ping, AFP, LUTCF, a 21-year MDRT member from Singapore who is part of Generation X, has seen the problem with making assumptions. Ping, who works with employees between the ages of 21 and 52, realized that her preconceived notions about her younger co-workers were not rooted in fact but in stereotypes.

“I thought younger people weren’t always clear about their direction in life,” she said. “It turned out that, with good communication and guidance, they have lofty aspirations.”

Ping says that there have been times when her Gen Z and millennial co-workers have had bad attitudes for what seemed like no good reason. With a little prodding, she came to realize that they were trying to get her attention but weren’t quite sure how to communicate that to her.

Voon Jin Goh, BSc (Hons), a one-year MDRT member from Singapore who works with Ping, says that technology is often blamed for confusion or disagreement between generations.

“Our more mature colleagues are less expressive via text messages,” said Goh, a millennial. “As such, it is easy to misunderstand a text message. However, such miscommunication also happens within people of the same generation.”

And when you have a difference of opinion with a co-worker, even if they’re of a different generation than you, don’t assume that your conflict is entirely due to that.

“People act differently because they’re different people, not necessarily because they belong to a specific generation,” Lee said.

The value of diversity

Multigenerational workplaces may have their challenges, but they’re not doomed to endless conflict. In fact, there are great benefits that come with having multiple age groups and the varying perspectives that come along with them.

“SHRM research has found that a diverse workforce leads to a more profitable company. Period,” Lee says.

There are many reasons for this phenomenon. Benjamin Loh, a professional millennial speaker based in Singapore, says a primary one is that multigenerational workplaces help avoid “group think,” in which everyone approaches a challenge or situation in the same way.

Instead, multigenerational workplaces breed what he has dubbed “generational empathy.” Working alongside people of different generations reveals different experiences and perspectives, which can be especially valuable when working with clients.

For example, Loh says people in their 20s and 30s may have a hard time helping clients plan for retirement, since such an event is so far away for themselves. But if they work with other advisors who are a bit closer to retiring, it may be useful to get their perspective on the situation.

“Sometimes the magic happens in the strangest of places,” Loh said. “The way I look at it is, the greater the diversity, the stronger the opportunity.”

Having a multigenerational workforce also makes it more likely that you’ll acquire a more multigenerational clientele. Most advisors reach out, at least initially, to their natural market, including former classmates, other parents from their kids’ school, or neighbors they see at the park. Chances are, they’ll be in a similar age demographic.

“It’s pretty critical that they have folks on staff who can relate well with their clients,” Lee said. “It certainly makes sense from an economic standpoint to build your business by adding clients of other generations and having employees of those other generations who can communicate well with them.”

As Rogers points out, “We all sell like we buy.” So younger generations who might be more comfortable with an online environment will be willing to sell online, while Rogers, who came up in the business when door-to-door sales were more common, still makes it a habit to drop in on small-business owners in his hometown.

It is not unlike a recipe. Together, the ingredients bring a far better outcome.

— Susan Paterson

Learning from each other

Peter Hill, ChFC, a 24-year MDRT member from Des Moines, Iowa, has seen the value of working with younger generations firsthand. His company maintains a relationship with nearby Drake University, hiring students as interns with the hope of converting them into full-time staff upon graduation.

To date, Hill says they’ve hired at least six former interns. These interactions with members of the millennial and Gen Z generations have taught him one important lesson: “The whole collaboration thing is huge,” he said, “as far as us all being able to learn from each other.”

Rather than dismissing her older colleagues’ ideas, Goh says that being newer to the profession means she values their experience and the lessons they’re willing to pass along.

“Our older colleagues have a system that they adhere by,” she said. “We can use the systems that are already developed and in place by our experienced colleagues to help ourselves get accustomed to such a routine from the very beginning.”

In other words, you don’t always need to reinvent the wheel when the original wheel-makers are sitting just a few cubicles over.

As for older folks learning from the younger ones, that’s happening as well — and not always on the computer screen. Susan Catherine Paterson, FChFP, a 17-year MDRT member whose staff ranges in age from 19 to 55, says that her younger colleagues have taught her to work at a faster pace, explore additional processes and embrace feedback.

“It is not unlike a recipe,” Paterson, of Loganholme, Queensland, Australia, said. “Together, the ingredients bring a far better outcome.”

Rogers agrees that working together is the key. “We have to always be willing to grow and learn and modify the way we do things if we are to work as a team,” he said.

Cheng Huann Yeoh, ChFC, CLU, an eight-year MDRT member from Singapore, has seen that in action. He said his company — he works with Goh and Ping — recently had a discussion about social media outreach.

The older generation didn’t think it was necessary and wanted to limit the amount of money going into the effort. The younger generation thought they should “go all out,” whatever the budget.

“A compromise was made, with key performance indicators and milestones to be fulfilled within a certain time frame before the budget was released in batches,” he said. “This allowed the committee to assure that traction had been made before more funds were released. At the same time, the younger ones could get the project started and were being held accountable for every dollar spent.”

It was a true win-win.

“The generational difference is mostly a plus,” Rogers said. “They have skills that I don’t have, they have talents that I don’t have, they have a different way of approaching things. It’s a whole lot better if we have an office with layers in it — layers of ages and talents.”

What are the generations again?

There are currently five generations in the workplace, but many people aren’t very clear on who fits where. Plus, generational breakdowns even vary by country or region. For this story, we relied on the cutoff points from Pew Research Center.

How to work across generations

As offices become more multigenerational in the next few years, it will be imperative that managers and supervisors make sure they’re encouraging collaboration and avoiding an “us versus them” mentality among generations. But how can they do that?

One popular concept is what Tony Lee calls “reverse mentoring.” As opposed to the traditional mentoring model, where an older or more experienced employee offers guidance to a younger, less experienced one, reverse mentoring encourages younger employees to assist their older peers.

He says topics can range from technological innovations or new business ideas to honest feedback on how an older employee is perceived. In turn, younger advisors can also learn techniques and processes from those who have “been there and done that.”

In an article in the Harvard Business Review, Jeanne C. Meister, the coauthor of “The 2020 Workplace,” also encouraged managers to create mixed-age work teams so members of different generations can learn from each other.

“Studies show that colleagues learn more from each other than they do from formal training, which is why it is so important to establish a culture of coaching across age groups,” Meister said. She also pointed out that these more informal relationships help avoid the perception of competition among colleagues.

Meet Gen Z

Move over, millennials. Generation Z, born in 1997 and later, is moving in. But who are these young people just entering the global workforce? It’s predicted that they will make up 24% of the workforce by the end of this year, so they are clearly a force to be reckoned with.

Tony Lee says these teens and 20-somethings actually have a lot in common with an unexpected group: baby boomers.

“The research we’re seeing is that Gen Z prefers face-to-face communication as opposed to Gen X and Gen Y,” he said.

He says this preference is likely due to Gen Z growing up with technology but not always knowing what to trust. Photos and videos can be altered; social media posts can spread lies and misinformation; fake news is everywhere.

“Gen Z tends to not really believe the information until it’s told to them face-to-face, because otherwise it could be wrong, it could be manipulated, it could be prejudiced in some way,” Lee said.

In 2017, INSEAD Emerging Markets Institute, Universum and the HEAD Foundation conducted a survey of Generations X, Y and Z. The survey found that Gen Z is a highly entrepreneurial generation: 25% of respondents are interested in starting their own business.

“They grew up on ‘Shark Tank,’ so they’ve seen how easy it is to come up with ideas and run with them,” Lee said. “They have lived in a booming economy for the past 10 years, so as far as they’re concerned, starting a business and making money is not that hard.”

The Center for Generational Kinetics conducted research in 2018 that highlights Gen Z’s reliance on feedback. Its “State of Gen Z” report showed that two-thirds of Gen Zers say they need feedback from their supervisor at least every few weeks to stay at their job, while one in five need feedback daily or several times a day to stay with an employer.

“This is a generation that is just finishing school where they take a test, walk out of the classroom, and their grade is posted on their phone,” Lee said. “They’re accustomed to knowing exactly where they stand all the time. So you want to have stronger communication channels than you would previously.”

And remember: These are generalizations. Each member of Gen Z is unique, just as millennials and Gen X before them. Whatever you do, treat each person as an individual and learn what matters most to them.